A child prodigy who copied the masters and painted the powerful, Angelica Kauffman (also spelled Kauffmann; 1741-1807) accompanied her father on a five-year journey through Milan, Venice, Parma and Naples. Johann Joseph Kauffman was a minor Swiss painter of portraits and frescos. His daughter was an international sensation.

Angelica Maria Anna Katarina Kauffman was a woman of many countries and myriad talents. Switzerland was her motherland and Austria raised her, Italy taught her its charms and England developed them. By age 13 she was receiving professional commissions from dukes and bishops. When she returned to Rome in her later years, the city gathered at her feet-Angelica Kauffman was lovely and larger than life-and the day she died, Rome mourned her as its own. It was the greatest funeral for a painter the city had seen since the death of Raphael. Neoclassic sculptor Antonio Canova directed the lavish event, and the entire Accademia di San Luca, of which she had been a member, paraded the streets in mournful procession.

During her lifetime, the strength of Kauffman’s artistic talents served as a bridge between the various countries where she lived and worked, allowing her to achieve noteworthy success in both England and Italy. After spending several years in Rome as an adult, Kauffman travelled to London in 1766, upon the invitation of Lady Wentworth, wife of the German ambassador to Venice. She stayed for 15 years. There, she wooed the royal family with her impressive abilities, requesting that King George III create London’s Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. As part of the group of artists who had pushed forward the plan, Kauffman was named a founding member in 1768, along with her dear friend Sir Joshua Reynolds, one of England’s greatest eighteenth-century painters, who served as the academy’s first president. Four works by Kauffman were included as part of its first exhibition; Swiss botanical painter Mary Moser (1744-1819), who was elected at the age of 20, was the only other woman artist who enjoyed similar acknowledgement.

Kauffman’s professional success was tinged with personal scandal. Conned into marrying a charlatan who had fraudulently posed as ‘Count de Von Horn of Sweden,’ Kauffman risked losing her hard-won reputation. Thanks solely to her connections with Reynolds, her staunchest supporter, she was able to avoid the social stigma of the separation and maintain her standing in eminent social and artistic circles. Only years later, after the would-be count had passed away, was Kauffman free to marry again. In 1781, she wed Venetian painter Antonio Zucchi (1726-1795), who had been working on commissions in England. Their subsequent return to Italy brought about Kauffman’s nomination as an honorary member of the Venetian Academy. While in Venice, several outstanding personalities visited her studio, including Grand Duke Pavel Petrovich, the future Russian Emperor Paul I.

In 1782, Kauffman and Zucchi settled in Rome, living in a mansion that previously belonged to their friend Anton Raphael Mengs (1728-1779), who was considered, during his era, Europe’s finest living painter. Intellectuals and Grand Tour travellers lured to Italy in search of passion and beauty regularly visited Kauffman’s salon, enraptured by the charm of their Swiss-born hostess, who led debates in German, Italian, French and English. Her facility for languages was matched only by her talent as a singer and musician. Canova frequented her home in Rome, as did German writer and statesman Johann Wolfgang Goethe, who wrote of Kauffman’s wealth and professional accomplishments in Italian Journey 1786-88: ‘Angelica has treated herself to the pleasure of buying two paintings, one by Titian, the other by Paris Bordone. They both cost her a lot of money, but since she is so rich that she can’t even spend the interest on her capital, and earns more every year into the bargain, it is a good thing that she should buy what not only gives her pleasure but also stimulates her painting. As soon as she got the paintings into her house, she began to paint in a new style, and tried to make certain devices of these masters her own.’

Kauffman had opened her home to the world, and the world, it seems, returned the favor. Her art became ubiquitous. The Industrial Revolution allowed Kauffman to become a champion of mass-produced objects: her oil paintings were copied as etchings and engravings and used to decorate pottery, medallions, snuffboxes, tea caddies and vases. Her mythological scenes, especially those depicting goddesses, nymphs and somewhat effeminate heroes, decorated famed European porcelain such as Wedgewood and Meissen. While Kauffman never actually decorated porcelain herself, the market still abounds with so-called signed pieces produced in the twentieth century.

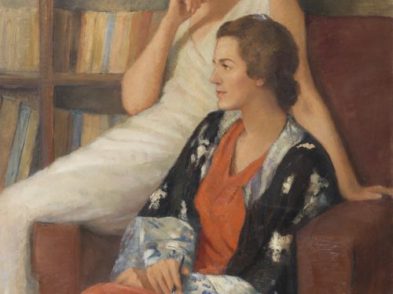

The eighteenth-century’s fondness for sentimentalism shines through her refined paintings, which are immersed in theatrical effects and archeological detail. Kauffman was also extremely successful with female portraiture, and many of today’s art historians consider her portraits of women superior to all her other works.

While in Rome working on her father’s commissions, in 1762, the year she was admitted to Florence’s Accademia dell’Arte del Disegno, she painted her Portrait of Benjamin West. An American-born history painter, West enjoyed much popularity in London, where he worked as one of King George III’s preferred artists. Theirs was a solid friendship and Kauffman produced several portraits of West, including the oil painting now in the Uffizi’s deposits. One year later, while still in Italy, Kauffman painted a frank self portrait, currently in storage. Palette and brushes in hand, she presents herself in a studio, sitting beside an open box of paints. Kauffman’s more idealized self portrait was chosen for exhibition in the Vasari Corridor.

Kauffman died on November 5, 1807. History has not sustained the reputation that she so carefully nurtured. Nevertheless, at the time of her death, her work was so esteemed that her estate was legally released from having to pay inheritance tax. During her funeral, two of her paintings were hoisted up and carried before the procession of mourners. Each citizen-whether master or servant-followed them to San Andrea delle Fratte, much like it had been on the day the world cried for Raphael.