An early morning visit to the exhibit The Renaissance Dream at the Palatine Gallery is like returning to a suspended state of sleep for an hour or so. It is truly a joy to experience such a cohesive grouping of works that offer close visual comparisons and suggest literary references. It’s a scholarly show, but contains enough high-quality pieces to be of interest to the public, and in my opinion is the best exhibit of 2013 in Florence.

Classical philosophers and Renaissance theorists after them reflected much on sleep and dreams. Hippocrates linked good dreams with good health; Aristotle connected dreams with melancholy and metaphor; Cicero, Macrobius and just about every other classical author expressed an opinion on the matter. All this was available to Renaissance humanists, especially to Marsilio Ficino, who, more than all the others, influenced the way dreams are depicted in visual arts. Ficino believed that when we sleep, the soul transmigrates: a kind of vacation for the soul in which it elevates itself from the body towards a superior and divine principle, hoping to reach divine, poetic or prophetic inspiration.

Ficino’s concept of dreams, which is part of the wider Platonic theory that shaped much of humanistic thought and art, is often conveyed through the juxtaposition of a nude, sleeping woman and a landscape, though it is not she, but the one who contemplates her, who might actually reach the state of divine inspiration. Exactly how this happens is not made entirely clear in the exhibit or catalogue, but requires the added knowledge of the importance of the consideration of beauty in Platonic theory (and perhaps a leap of faith, too). Plato posits that ‘true love is a desire for perpetual possession of the Good and Beautiful,’ which Ficino extends by saying that true love is directed at God, but the first step towards getting there is appreciation of beauty and physical love, after which one proceeds to the soul, mind and, finally, to God. All this was used to justify numerous titillatingly illicit relationships in the Renaissance, such as that between Michelangelo and Tommaso Cavalieri, or between Francesco de’ Medici and Bianca Cappello, both of which are represented by works in this exhibition.

Lorenzo Lotto Allegory of Chastity

Much theory backs the paintings shown at the Palatine exhibit, and the curators spend not nearly as long as I have to show you the art, which, although grouped by visual and iconographical type, in a rare feat coheres as a whole across the sections. Along with works from local and Italian museums are a remarkable number of excellent loans: the Dosso Dossi Allegory with Pan from the Getty Museum and the Raphael Vision of a Knight from London’s National Gallery particularly stand out.

One could almost miss the undisputed star of the exhibit, Lorenzo Lotto’s small panel of the Allegory of Chastity, from the National Gallery of Art in Washington (ca. 1506). To see this enigmatic painting in person is truly a dream, for no reproduction contains sufficient detail and number of colours to render its delicacy. A woman sleeps against a laurel tree trunk in a landscape and, above, a putto showers her with tiny white flowers. Representing Chastity, she is contrasted by a satyr couple on either side in the foreground—a satyress spying on a drunken and aroused satyr who attempts to get the last drops out of a jug. Look at the treatment of light in this painting, which could be either dusk or dawn. I vote for morning, because Lotto creates the most calming, soft light that seems to just come up from the horizon, starting to brighten the leaves on the trees in the right of the painting, which seem almost afire. Meanwhile, the detail of the tiny white flowers, each petal a daub with a little paintbrush, was added last of all, and is so incredibly delicate. This painting is very close to Giorgione in elements like the tree trunk and the chromatism.

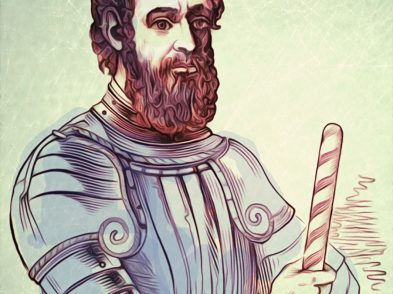

Giorgione, in fact, is missing in this show, perhaps because none of his known paintings show a dreaming figure of the iconographic sort featured in this exhibit, though it is likely that he depicted some, for there are two prints that reproduce them. One is Giulio Campagnola’s marvelous dotted print of a reclining nude in a landscape, not in the exhibit. The second, shown here, is Marcantonio Raimondi’s engraving from around 1508, commonly called The Dream of Raphael, perhaps because much of Raimondi’s work does reproduce themes invented by Raphael. However, in his early years he also took in Venetian inspirations, and this design says more about Giorgione than it does Raphael, mainly in the figure seen from behind, which is very close to the one Campagnola rendered after Giorgione. Here the subject is a nightmare, with strange hybrid animals trotting out of an inky lake—these could only be influenced by Bosch, two of whose works were present in a Venetian collection probably already by 1505, before this engraving, and presumably before the painting upon which it is based.

Marcantonio Raimondi The Dream of Raphael

The print is displayed next to a much later rendering of the same subject with a very different composition: Giorgio Ghisi’s engraving of 1561. Here is a history of printmaking summed up in less than a meter, an opportunity to compare the techniques up close. Raimondi uses hatching at 90 degrees and with space between the lines the size of a rough linen waft, while by the time Ghisi was working, the technical aspects of engraving had evolved to include many different types of lines and flecks. The earlier print is technically excellent nonetheless, and the grayish hue seems in line with Giorgione’s paintings and the subject of dreams. In the depth of Ghisi’s black background, if you practically press your nose to the glass, you’ll be rewarded with visions of strange demons and owls.

Between Lotto, Raphael and Dossi, with shadows of Michelangelo and Giorgione, an exhibit of this caliber helps the viewer understand how contemplation of these works might truly have led to Platonic inspiration.