Florence is a city of stone, of imposing civic, religious and domestic architecture—where power and wealth are communicated in girth and in height. Massiccio—solid, hefty—is the adjective used to describe so much in Florence—the architecture but also the figures in paintings, its works of literature. One must only think of the Duomo, Palazzo Vecchio, the tower houses, the Renaissance homes of the Strozzi and the Medici, Giotto’s campanile. They are power and confidence, boldness and daring embodied.

A view of Palazzo Pitti in the Boboli Gardens / ph. @marcobadiani

It stands to reason that the monumental Boboli Gardens, initially laid out in the 16th century when the Medici were eager to communicate their newfound official power, would be a reflection of the city’s long-standing attitude about building—bigger, heftier, taller, better.

The large green space running along costa San Giorgio behind Palazzo Pitti had been known as “Boboli” long before the Medici moved in, and was a major selling point for Duke Cosimo I and his Spanish princess wife, Eleonora di Toledo, who yearned for a large garden in the middle of her adopted city of stone. Work began in the 1550s and Boboli quickly became known as the quintessential Italian garden—harmonious, geometric, balanced—a powerful symbol of man’s ability to triumph over nature. It is a place, to paraphrase Zadie Smith, designed to make you feel shy and underdressed, no matter what you are wearing.

There is, however, an alternative Boboli—a lighter, less massiccio version—if you have the time to spend seeking it out.

Grottos

Annalena Grotto / ph. @marcobadiani

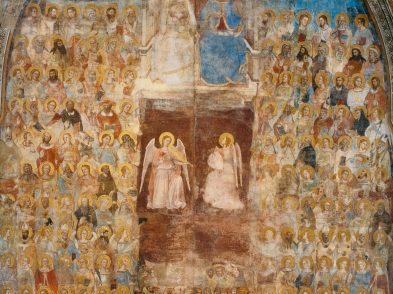

There are several grottos in the Boboli Gardens, each offering a glimpse into the magical world of the Medici and their interests in alchemy, mythology, art and spirit. The largest of the grottos is the Grotta Grande, designed for Francesco I de’ Medici in the 1580s by court architect, engineer and all-around-genius, Bernardo Buontalenti. Created as a place for meditation and reflection, the grotto’s first room boasts a circular hole in the ceiling that would have originally filtered light onto a glass basin filled with darting fish before then bouncing up onto the walls, which are imaginatively decorated with human figures, architectural ruins and man-made stalactites in the shape of tree branches. The whole effect would have caused a (very likely welcome) escape from reality for the Medici prince and anyone else fortunate enough to enter the precious space. Today we can still admire the exquisite decorations made from coral, exotic shells from the Indian Ocean, hematite and enameled glass. The Grotta della Madama is nearby, but you will have to take the small secondary paths to reach it, as it is a bit less conspicuous than Buontalenti’s masterpiece; and the Annalena Grotto, located near the eponymous gate, is a neo-classical dream come true.

Upper Botanical Garden

The exotic Upper Botanical Garden / ph. @helencfarrell

During the Grand Tour, guidebooks touted this space as one of the city’s must-see attractions, referring to it as a “Little Eden” where you could wander to your delight, smelling and gazing upon the extensive collection of rare flowers and plants. The original 18th-century project included a vegetable garden dedicated to edible plants and rare exotic species, such as pineapples, which were such a rarity that the garden was nicknamed the Giardino degli Ananassi (Pineapple Garden). Tucked to one side of the sweeping viale dei Cipressi, this (relatively) small botanical garden is still a true hidden gem in the Boboli, though only open for a short time in the spring each year.

Ragnaie

These groves made of densely-planted tall trees were a staple of 16th-century Italian Gardens, and were used in the hunting of small birds—a popular pastime for the nobility. Following the path of Boboli’s ragnaie will allow you to sneak off into the lovely wooded areas that offer a quiet and shady respite from the bustling, monumental avenues.