The Artemisia UpClose restoration-in-progress is now on public view at Casa Buonarroti thanks to the generosity of international art patrons. Fridays offer an exclusive opportunity to spend time with Artemisia Gentileschi’s Allegory of Inclination, a tribute to Michelangelo, while learning from the restorer in situ.

Come closer!

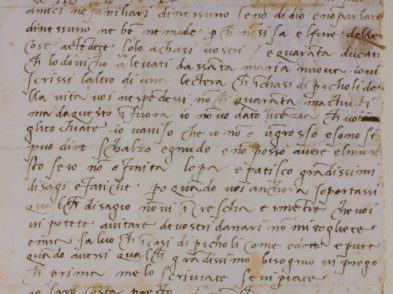

Conservator Elizabeth Wicks uses a digital microscope to examine painting’s condition

ph. Olga Makarova

Conservator Elizabeth Wicks uses a digital microscope to examine painting’s condition

ph. Olga Makarova

Conservator Elizabeth Wicks uses a digital microscope to examine painting’s condition

ph. Olga Makarova

Conservator Elizabeth Wicks uses a digital microscope to examine painting’s condition

ph. Olga Makarova

If you’ve never been to Casa Buonarroti in via Ghibellina, go there. If you’ve been, go again because, this time—and for a short time only—your “host” will be the artist you’ve been waiting a lifetime to “meet”. Artemisia Gentileschi—or better said, her Allegory of Inclination—has been removed from its neck-craning position on the gallery ceiling and is now on public view whilst under restoration in the museum’s model room, so that the art-loving public can monitor its progress close-up. Diagnostic tests have been underway since the painting’s descent from the ceiling at the start of October and on Fridays—from now until April—museum guests can ask head restorer Elizabeth Wicks questions while on location at her worksite.

The restoration in-progress can be viewed on other weekdays as well, albeit without the conversation with the conservator option, given that Dr. Wicks’ maintains quasi-religious silence as she continues with delicate manual restoration or diagnostics on Artemisia’s 1616 work, in the shadow of Michelangelo’s wooden model that was designed for the façade of the church of San Lorenzo, which remained nothing more than a twinkle in the master’s eye.

The project Artemisia Unveiled, created in conjunction with the Casa Buonarroti Museum and Foundation, is supported by Calliope Arts, a not-for-profit organisation based in Florence and London that promotes public knowledge and appreciation of art, literature and social history from a female perspective, and British art collector Christian Levett, founder of the Mougins Museum of Classical Art in France and the Levett Collection home-gallery in Florence, featuring artworks by major female Abstract Expressionists.

The science and the show

By order of Lionardo Buonarroti, Artemisia’s nude allegorical figure was covered up by Baldassare Franceschini, the artist known as “Il Volterrano”, in an effort to protect the owner’s wife and children from being exposed to a figure that might dent their decorum.

“From its onset, an important aspect of this project has been to create a virtual image of Artemisia’s original work, on the premise that the over-painting will not be removed,” explains Dr. Wicks. “The first reason is that Il Volterrano’s repaints are considered historic and part of the painting’s setting and life story. Secondly, there is only a 70-year difference between Artemisia’s painting and the ‘censoring’ draperies and veil. It’s a thick layer of paint, with impasto. It may turn out that the two artists’ layers are very strongly bonded, and if that is the case, we absolutely cannot put the painting at risk.”

Once restoration science has had its fair share of time with the painting, Casa Buonarroti is poised to host an Artemisia-centred exhibition, scheduled to run from September 2023 to January 2024. “The show will spotlight conservation findings and explore the context surrounding the painting’s creation, including the significance of her Florentine debut and her key relationships with Grand Duke Cosimo de’ Medici and the city’s cultural milieu,” says museum director Alessandro Cecchi.

“We’d like to look at the project as the start of something bigger,” co-donor Christian Levett adds. “Beyond the restoration of the artist’s Buonarroti painting and its subsequent exhibition, Artemisia CloseUp includes a refurbishment of the museum entrance, the renewal of its signage and the redesign of the gallery room’s lighting. This museum has an amazing story to tell and we want to shed more light on it, literally.”

Once with her

When approaching the Artemisia in person, note the star near the Allegory’s forehead. Some say it’s the North Star, set in the sky to guide the creative process. An artist’s “inclination” is what drives him, or in this case, her, to put brush to canvas or scalpel to stone, and this figure was meant to tribute the virtues of Michelangelo, as one of 15 paintings commissioned by Michelangelo the Younger, Michelangelo the Great’s grandnephew, whose dream was to transform the five Buonarroti buildings into a home-museum or, more than that, it was to become a seventeenth-century temple to Michelangelo, whose legend was quickly growing. “The Great” was not good enough, as the gallery ceiling’s central artworks suggest, he was to be Il Divino, an artist who had achieved godly status Michelangelo, “the Divine”.

That transformation took some 30 years and Artemisia’s painting was the first of its series. If there were ever a time to be painting stars, it was in 1616 and Casa Buonarroti was the place. Galileo frequented the Buonarroti home and Michelangelo the Younger was so bold as to include the scientist’s image on the frescoed ceiling of his “studio”, amongst groups of history’s greatest minds—from antiquity to the then-present day—despite the unpopularity of his Earth-revolves-around-the-Sun theories. Artemisia finished her own painting the same year Galileo’s heliocentrism was declared heretical. Also in 1616, she became a member of the nearby Accademia delle Arti del Disegno; her fellow academicians included Michelangelo the Younger and, more famously, Galileo Galilei himself. The compass Artemisia’s figure holds is thought to be a nod to Galileo’s discoveries as she and the scientist were friends and they corresponded until Galileo’s death in 1642.

That Artemisia, who learned to read and write in Florence, frequented the most illustrious minds of her time should not surprise us; she had grand-ducal favour. (The star may also allude to Cosimo II, fittingly named for the Cosmos because, after all, as Vasari states, the Medici were “terrestrial gods”.) We should also not be shocked that Artemisia, from her early days onwards, was immensely skilled at self-promotion, hence it is not unreasonable to suggest that she wouldn’t have minded for the virtue she depicted to be forever associated with her own name, in a society where women were not seen as “driven” to do anything that would last through the generations, except for actually bearing them. Although her tribute to Michelangelo was not defined as a self-portrait, many assume Artemisia’s own face (and body?) was similar to that of her Allegory. In this window of time, from now until spring, make sure you visit Artemisia’s work at Casa Buonarroti and, while you are there, see if she will tell you that secret—among the many others Artemisia UpClose is sure to reveal.

Who’s involved?

The project brings together restoration scientists, technicians, photographers and filmmakers to compile, analyse, document and share findings. The project’s players include: curatorial management and monitoring: Casa Buonarroti Foundation and Museum and Archaeological Superintendence for the Fine Arts and Landscape for the Metropolitan City of Florence. Donors: Margie MacKinnon, Wayne McArdle and Christian Levett. Research: Italy’s National Research Council (CNR) and National Institute for Optics (NIO), Teobaldo Pasquali for X-ray and radiographs, Ottaviano Caruso for diagnostic images; Massimo Chimenti of Culturanuova s.r.l. for digital image creation; Olga Makarova for video and reportage photography. Project coordinator: Linda Falcone. Media partners: Restoration Conversations and The Florentine.