For his major exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi, Olafur Eliasson has decided to play with the building. “Play” may not be the most appropriate word, but Eliasson’s immersive installations do not lean heavily on the word “art” either. Eliasson turns fresh light on existing situations and, in the process, asks searching questions of his audience about their responsibility to the planet they occupy. But to see the possibilities that his work puts forward, you have to keep moving.

New perspectives on familiar locations are Eliasson’s speciality. Entering the courtyard of this famous building provides a surprise: an oval-shaped steel canopy hovers overhead, partially obscuring from view the formal Renaissance rhythms of the architecture. Indeed, this curious intervention sits where normally the sky would be. Rather than being a closed form, however, the elliptical cover consists of numerous strips of printed textile and polypropylene; as natural light fades, an artificial yellow light takes over, percolating through the steel perimeter framework and altering the feel of the interior space.

With this work, which is called Under the Weather, Eliasson introduces the visitor not only to this exhibition but also to different ways of experiencing art. In fact, the “art” aspect is perhaps the least obvious. More immediate are the varying sensations of spaces that this Danish-Icelandic artist, architect and design superstar helps the visitor to bring about. For instance, when that person stands still on the edge of the courtyard and looks up, the pattern stretched out above is static and a little unimpressive. But step forward, keep moving, and new patterns take shape that seem to expand, contract and converge, like moire effects in fabrics—or how clouds shift and change with the atmosphere in the course of a day. Movement is key, Eliasson implies, and that action can only come from each individual visitor. The artist shares responsibility for opening each new perspective with his audience: their gestures are interdependent.

Eliasson’s places ecology, sustainability and natural resources at the core of his work. Electricity is solar-powered and metal recycled. His principal materials are light, water, space and temperature, choices informed by the extreme conditions of his native Scandinavia. With his father he travelled in Iceland and developed a profound appreciation of the natural resources, dramatic contrasts of climate and the emotional impact of the ancient rocky landscape. He came to prominence in 2003 with the Weather Project at London’s Tate Modern, where a warm orange, sun-like semi-circle was hung high above the gallery’s vast entrance hall. Completing the piece was a mirror attached to the ceiling: it reflected the warm orange glow so that it filled the soaring interior. Over two million visitors came to see the installation—and to see themselves in the high-up, faraway mirrors. Eliasson is fascinated by how people react on these occasions. In London, where weather dictates so much about the city, some had picnics on the concrete floor beneath the artist’s artificial sun; others staged political protests (the Iraq invasion had recently taken place); and many simply sat in groups and individually to absorb the experience and record it for friends.

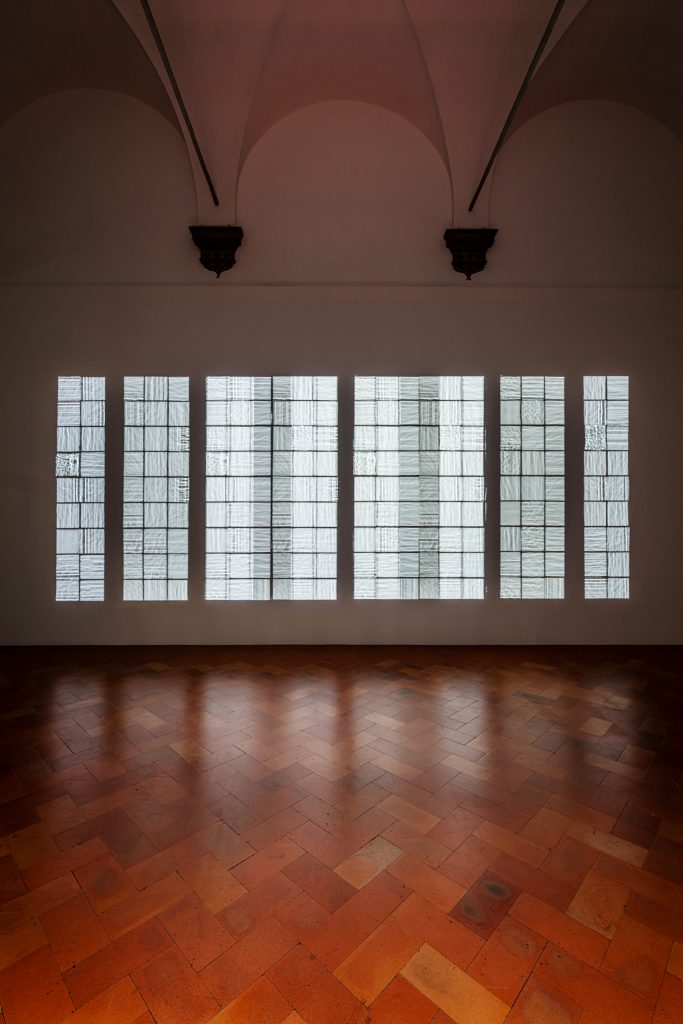

At Palazzo Strozzi, Eliasson also makes use of the building. The first three rooms bring to attention the glass in windows around the courtyard. An element that is invariably overlooked becomes the focal point. Many panes date back in time and bear traces of outmoded means of manufacture. So magnified against interior walls by strong exterior lamps is a floor-to-ceiling frieze of grids and rippling surfaces that recapture long-ago processes, maybe marks left by the makers’ breath. Beyond the spectacular effect is the realisation that, by relatively simple means, Eliasson makes “immaterial” space almost tangible, reminding viewers of the scientific truth that emptiness does not exist and that matter fills the environment with which we constantly interrelate and in which our presence brings about ceaseless change.

The earliest piece on show is Beauty (1993), in which precisely this idea of making phenomena tangible is the theme. The one area of illumination in an otherwise dark room comes from light trained on water drizzling from an unseen source in the ceiling. Spectral colours appear suspended in the space on a curtain of mist because these simple elements imitate how rainbows occur. But no two people are likely to see the colours in the same way. It is a question, once more, of perception: the order depends on the triangulation of light, droplets and the height of each pair of eyes.

Once again the visual quality is immediate, so that time to pause and think so this is art does not occur. There is an instant magic to seeing and hearing water: in 2008, Eliasson created four waterfalls cascading from scaffolding towers over 30 metres tall in New York’s East River, making an unnatural event appear natural. Eliasson is keen to make fluid the boundaries between art, architecture and everyday experience, so that they all become spaces that welcome and hold people. They feel neither challenged, nor “put to work”, in the manner that many find off-putting within conventional museum contexts. Instead, audiences collectively or individually find their own points of entry without being hurried or prompted. Hence the title chosen for this show: Nel Tuo Tempo. Eliasson wants no one to feel excluded.

A significant element in that encounter is colour. Several rooms (and each room contains a separate project, many conceived for Florence) are saturated with colour, the most striking being Room for one colour (1997). Monofrequency lighting from ceiling lamps emits only yellow light. Apart from the strips overhead, the space is empty. But since nowhere is empty, revelation exists within the actions of every person crossing the threshold. We are used to sodium street lighting at night, but the monochromatic effect indoors impairs normal vision. As when watching rainbows, everyone sees slightly differently inside this vastly restricted scale, and all sense a change to their perception of space and detail. Pleasure is not guaranteed—it never is—yet walking through the room reveals colour generating activity and movement facilitating new awareness.

Eliasson enjoys experimenting with physics and materials. His studio in Berlin is a kind of laboratory with teams of engineers, academics and craftspeople. That is where ideas are formed and tried: some fail, while others filter into objects, architecture and exhibits. Kaleidoscopes bounce back endless reflections onto the viewer and mirrors project inverted and reversed images of the self. Geometric shapes are projected from a lamp placed to cast a “wunderkammer” network of interconnecting angles. The artist also uses virtual reality to extend the physical experience of space into the purely digital dimension.

There is no escaping the fairground nature of this exhibition. Each room offers a new attraction and every project appears designed with Instagram posts in mind. Once invited to see their surroundings in a different light, most visitors photograph it—and themselves within it. That adds a further layer of artificiality to the encounter. Yet play and learning go together, and Eliasson articulates a broader purpose, asking people if they wish to engage intensely with the world to reflect on their own responsibility within that environment. Are they living in a picture, such as art traditionally assumes, where every transaction is free of consequences? Or is art a representation of our place within the reality of shared existence? Actions have results and those with whom we share that space might not thank us for them.