The celebrations of the coronation of King Charles III in London in May had me wondering whether similar ceremonies had taken place in Italy in the past. Research led me to discover that indeed they had. One of the most elaborate occasions was when Napoleon Bonaparte declared himself as the King of Italy in Milan Cathedral on May 26, 1805, after his brother, Joseph, had refused the honor, not wishing to renounce his rights to the French throne. This took place almost six months after Napoleon had been crowned French emperor in Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris in the presence of Pope Pius VII on December 2, 1804, a scene that was immortalized in the famous painting by Jacques-Louis Davide. Reports of the time claim that the Milan coronation was even more solemn and grandiose than the Paris version. The sun was shining and the church bells pealed out throughout the city, while the square in front of the church was packed with spectators, all eager to watch the proceedings. French and Italian military units fired cannon volleys into the air.

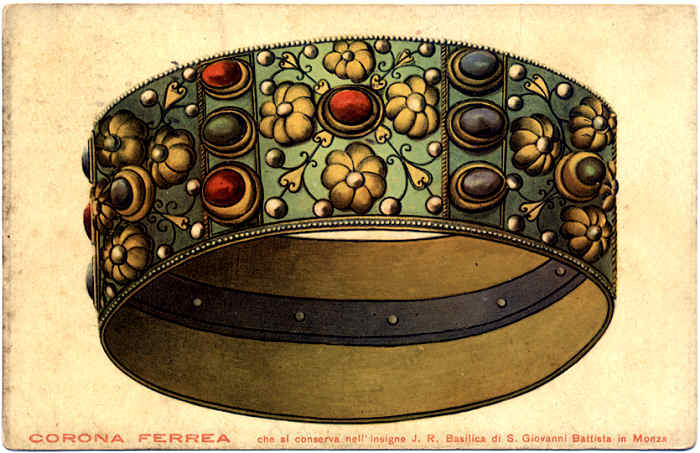

Both sumptuously dressed, Napoleon’s wife, Joséphine de Beauharnais, and sister, Elisa Baciocchi, were the first to arrive at the cathedral and take their places in the golden gallery, which had been purpose-built for the event. Next came a procession consisting of 16 bishops, 10 vicars and the city’s cardinal. On May 22, three carriages escorted by 50 cavalrymen had been sent to bring one of four crowns to Milan. The Iron Crown of Lombardy (in Italian, Corona ferrea) is revered as a holy relic and is housed in Monza Cathedral to this day. According to one of many legends, the small crown is said to have been ordered by Saint Helena for her son, Constantine the Great, and encases a beaten nail from the cross used during Christ’s crucifixion, which she had found in the Holy Land, thus giving the crown its name. Pope Gregory I is thought to have gifted it to Theodelinda, queen of the Lombards who, in turn, donated it to the church in Monza around 594.

The crown’s external circle unites six segments of partially enameled beaten gold held together with hinges. Twenty-two protruding jewels in a cross and flower pattern embellish the diadem. The crown was used in Charlemagne’s coronation as King of the Lombards in 774 and Holy Roman Emperors were subsequently crowned with it as kings of Italy for centuries.

To enable Napoleon to arrive from the Royal Palace to the cathedral in full view of the crowd, a long, open-sided, decorated gallery was erected, so that the ruler could enter through the main door over which the kingdom’s coat of arms had been hung. Wearing the Imperial Crown, a green velvet mantle with a long train, and carrying the scepter and the hand of justice, he walked to the throne under a canopy held over his head by the clergy to the accompaniment of 250 musicians and choir. He was followed by other family members and notables carrying the royal regalia of Charlemagne, Italy and the Empire, which the cardinal consigned to him. Napoleon moved to the altar, took the Iron Crown, placed it on his own head on top of the Imperial Crown, and declared “God has given it to me; beware he who touches it”.

The Iron Crown was returned to Monza on May 27, while celebrations continued in the city until the end of the month. On June 6, Napoleon created the Order of the Iron Cross and on June 7, 1805, he appointed Josephine’s son, Eugène Rose de Beauharnais, as Viceroy of Italy. He would reside in Monza.

Following the collapse of Napoleon’s Kingdom of Italy, the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia was created as part of the Austrian Empire in 1815 by a resolution of the Congress of Vienna in recognition of the Austrian House of Habsburg-Lorraine’s rights to the former Duchy of Milan and Republic of Venice. It would last five decades. During this period, the Hapsburg emperors of Austria used the Iron Crown as the crown of their Italian kingdom, ending with the last Hapsburg king, Ferdinand I of Austria, being crowned with it in 1838. After the Second War of Independence in 1859, when the Austrians were forced out of northern Italy to Vienna, they took the Iron Crown with them. It remained there until after the Third Italian War of Independence, when it was returned to the Italian House of Savoy in 1866, but no King of Italy of that dynasty was ever crowned with the Iron Crown. This was partly because of the “Roman Question”, whereby the Papal States were deprived of their Adriatic provinces and were restricted to the territory around Rome in 1860. This led the Pope to excommunicate King Victor Emmanuel II, while later neither King Victor Emmanuel II nor King Umberto I wished to use the Iron Crown because of its status as a relic within the Church. The Iron Crown was nevertheless carried during Umberto I’s funeral procession after his assassination.