“A Woman’s Place is in the home” wrote a disgruntled and protective mother in an anonymous letter to the governor of the Banca d’Italia after her son failed to get a job following an interview with the bank. She believed that the reason for his failure was that the bank employed far too many women and that they would have been better sticking to the domestic environment rather than grabbing employment from their menfolk. What is surprising is that this letter was written in 1965, by which time the bank, already at the forefront as an employer and supporter of female emancipation, was providing women with equal opportunities and pay, as well as beginning to give them positions of responsibility within its hierarchy in a progressive approach that was clearly not shared by all. This information is provided in a fascinating short video that accompanies the current exhibition Towards Modernity: Women in the Banca d’Italia’s Art Collection at the bank’s headquarters in Florence.

This free exhibition provides an opportunity to enter the beautiful building in via dell’Oriuolo and to climb the imposing spiral staircase to the top floor. The bank opened to the public in 1871 when Florence was the capital of a united Italy for a short spell between 1865 and 1871, something that is reflected in the grandeur of the interior.

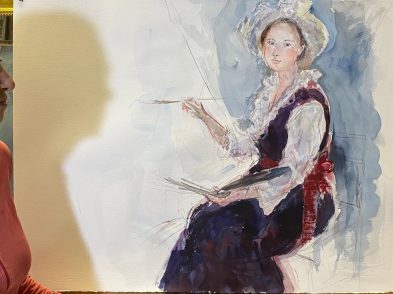

As a prelude to paintings of and by women, as mothers, muses, decorative creatures, and subsequently liberated beings and painters in their own right, there is a display on the ground floor celebrating Dante’s Beatrice with a painting by Raffaello Sorbi (1863) depicting their first encounter and three precious editions of the Divine Comedy. Varied in scope, the exhibition includes paintings dating to between 1870 and 1950 from the bank’s sizeable collection. Different currents in Italian art are displayed as well as changing ideologies, both social and political, and the growing emergence of women as artists in their own right. We see women portrayed by men as mothers and “apprentice” mothers: a little girl mothering the doll on her lap as she emulates her Junoesque mother in Luciano Ricchetti’s Le due mammine (1940), which reflects the idealization of motherhood under fascism. Silvestro Lega’s nursing mother in Maternità (1881-82) is an intimate portrait that transcends its time. There are decorative ladies of leisure in impressionist settings, followed by paintings that show women’s growing sense of self-definition and identity. In an unattributed painting of 1906, Giovane naturalista, a young woman holds a shell, absorbed in her own thoughts, examining it with the curiosity and intensity of a scientist. We see women both separated from the male gaze and playing with it, relaxed and comfortable in their bodies. Marcello Dudovich’s glamorous lady walking her greyhound on a windy beach (1922) strides with athletic confidence. Women do not need to be idealized or idolized: Alberto Magnelli portrays a woman in casual pose (1924-28), her eyes shut, sitting on the ground in stockinged feet, one leg crossed beneath her.

Female painters make an appearance too, with still lives and depictions of the naked female figure. Exhibited side by side are two works showing a pot of geraniums, each tenderly painted in the 1920s by women artists from very different backgrounds. Leonetta Cecchi Pieraccini came from a prominent Sienese family. Married to the influential art critic Emilio Cecchi, her brother, Gaetano, was the first mayor of Florence after the Second World War, yet she became a respected artist in her own right. Her contemporary, Pasquarosa Bertoletti Marcelli, came from more humble origins. Born in Anticoli Corrado, a village near Rome referred to as a “town of models and beautiful women”, she started her working life as an artist’s model in Rome before later becoming a painter. An exhibition opening on January 12 at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art in London, Pasquarosa: from Muse to Painter, is set to celebrate her work. Pasquarosa is one of the “Flood Ladies”, a group of international female artists who contributed artworks to Florence following the catastrophic 1966 flood as a mark of solidarity and to help repair the psychological damage done by the flood. Back in 2014, the Advancing Women Artists Foundation headed an effort to preserve, exhibit and acknowledge the contribution of these women. Their paintings are now in the permanent collection of Florence’s Museo Novecento.

When I mentioned the mother’s letter shown in the video at the Banca d’Italia exhibition to friends in Italy and the UK, they informed me that the same attitudes persist today. The bank acknowledges that there is still a way to go to achieve parity, but stories such as Pasquarosa prove inspirational: a Lazio peasant girl born in 1896 is celebrated in 2024 in a London museum praised for quality exhibitions. Financial Times chief art critic Jackie Wullschläger singled out the Lisetta Carmi shows held at both the Estorick and Villa Bardini in Florence as among the ten “best art exhibitions of 2023”, citing Carmi as her “discovery of the year”.

Increasing visibility for women artists in Florence and beyond helps to rewrite the history of art and widens the scope for female ambition, showing that a woman’s place can be wherever she wants it to be.