Picture the scene: Florence, 2002. Palazzo Serristori. Antonio Natali, director of the Uffizi Gallery, notices something wrapped in plastic and rolled around a lamppost. He calls over restoration expert Muriel Vervat and together they unroll it, discovering that it is a painting, its colors obscured by thick, dark mold. The smell is overwhelming.

The painting’s subject incomprehensible, they search for any identifying qualities, anything that might give them a clue as to what may be below the layer of black mold, but they find nothing. Then, a breakthrough: a small tag with an inventory number. The records entry reads ‘Painter from the XVII century; Pluto kidnapping a nymph.’

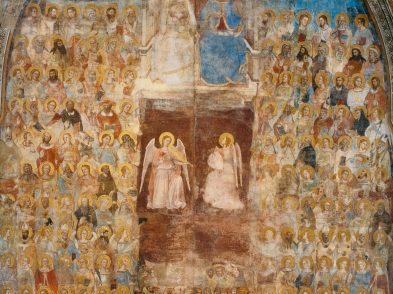

Now cross the river to the Uffizi Gallery. Room 42, the Sala della Niobe, in need of restoration. The splendid room was built in 1770, by order of Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo of Lorraine, to house the statues of Niobe and her children, which were discovered in 1583 in the Tommassini vineyards in Rome. The statues depict the myth of Niobe-the proud mother who boasted of having more children than the goddess Leto. Enraged by Niobe’s pride, the goddess punished her by killing all of her sons and daughters.

According to the first official guide to the Uffizi, the Real Galleria di Firenze, written by Luigi Lanzi in 1782, the statuary was flanked by a group of monumental paintings, including Justus Suttermans’ The Florentine Senate Swearing Loyalty to Ferdinando II de’ Medici, two Scenes of Henry IV by Peter Paul Reubens, and The Rape of Proserpina by Giuseppe Grisoni. The Reubens canvases had been restored and rehung after they were damaged in the 1993 mafia bombing. Then restoration of the Suttermans canvas in 2001 had triggered the desire to see the entire Sala di Niobe returned to its original splendor-a room that, according to Lanzi, emanated regal magnificence and rivalled the salons of other European royal courts.

The only hold-ups to the complete restoration of the Niobe Room were funding and the fact that the Grisoni canvas was missing. Without the immense 6m x 4m painting, the room would be out of balance, its original harmony lost for good. It was then that the pieces of the puzzle began coming together. Could the ruined canvas from Palazzo Serristori be Grisoni’s masterpiece? The period, seventeenth century, and subject, ‘Pluto kidnapping a nymph,’ were right.

Enter Countess Simonetta Brandolini d’Adda-founder and president of U.S.-based nonprofit organization, Friends of Florence-who received a phone call from Natali. Could she come by the Lungarno palazzo to have a look at something they had just found?

With the tar-colored canvas now laid flat, and with Brandolini and Natali looking on, Muriel Vervat carefully took a gasoline-soaked cotton rag and began to pat at the mold on the top layer of the canvas.

What emerged was striking: it was the terrified face of Proserpina, who, in Vervat’s words, seemed to be crying out ‘Please, help me!’ In a courageous, almost instinctive move, Brandolini went into action to find a way to raise the funds to restore what she and her colleagues immediately considered Grisoni’s lost canvas. Because of the painting’s extensive damage, Brandolini knew the restoration project would not be an easy sell. However, in the end, her conviction paid off: Friends of Florence not only raised the money necessary to bring the masterpiece back to life, but continued to raise a whopping $500,000 to restore all of the statuary in the Sala della Niobe. Vervat got straight to work.

Thanks to uncharacteristically detailed archives, Vervat discovered that Grisoni’s work had been commissioned by the Medici in 1731 not as a painting but as a tapestry to be woven in the family’s workshop. Indeed, we can still find the exact replica of Grisoni’s Rape of Proserpina as a tapestry hanging in Palazzo Pitti. The fact that the tapestry’s model was then hung in the most prominent gallery in Florence, rather than being destroyed once the tapestry was complete, is testimony to its stunning character.

After receiving preliminary work in the Le Cacce laboratories in Palazzo Pitti (also restored by Friends of Florence in 2003), the painting was taken back to its original home in the Uffizi’s Sala della Niobe so that it could be restored in its proper light. A team of 11 restorers was assembled-all women, all young, all highly qualified. Vervat insisted that the restorers truly function as a team, with each member having the unique opportunity to take responsibility for her own work, rather than proceeding as mere assistants to the restoration expert, as is traditional.

Vervat believes that each restorer worked twice as hard knowing her work would directly affect and influence the work of her colleagues. ‘I wanted to foster the connection between colleagues and allow each one direct access with the art historian on the project. This is something that rarely happens in our field where young professionals are often limited by their relationship with the expert they are working under,’ said Vervat.

The unique collaboration spilled over into the restoration of the room as whole, as art historians, restorers and museum administrators began working together for a common goal: Bringing the Sala della Niobe back to its former glory.

After two years and 6,000 hours of work, Grisoni’s Proserpina was brought back to life. The restored masterpiece was unveiled in 2004, transformed from a blackened, ruined canvas to a brilliant painting bursting with energy and color.

Friends of Florence responded to Proserpina’s cry, and she stands today as a testimony to tenacity, courage, collaboration-and faith.

For more information on this and other Friends of Florence projects, visit www.FriendsOfFlorence.org. A book on the complete restoration of the Sala della Niobe will be released in early 2009.

The restoration of the Sala della Niobe was made possible by Friends of Florence with major grants from the following individuals and associations:

Statue I – Niobe Mother with Youngest Daughter

Elissa and Edgar Cullman, Jr.

Statue II – Oldest Daughter of Niobe

Becky and Frank Meyer for Ann O’Brien

Statue III – Oldest Son of Niobe

Brandon Fradd

Statue IV – Niobe Son Climbing a Rock Face

Brandon Fradd

Statue V- Son of Niobe, Once Thought to be Narcissus

Brandon Fradd

Statue VI – One Son of Niobe

CA Community Foundation – The Stone Family

Statue VII – Son of Niobe Fallen to One Knee

Linda and Vincent Buonanno

Statue VIII – One of the Daughters of Niobe

Jill and Richard Almeida

Statue IX – One of the Sons of Niobe

Melanie Cabot and Orna Shulman

Statue X – Son of Niobe

Mary Mott and Gordon Simmering

Statue XI – Youngest Son of Niobe

Tony Mantuano

Statue XII – Last Dying Niobid Son

Jon Stryker

Statue XIII – Muse, Once Thought to be a Niobe Daughter

Chicago Chapter

Statue XIV – Tutor of the Niobe Children

Sarah Wiggins

Statue XV – Selene Goddess of the Moon, Once Thought to be a Niobe

Friends of Heritage Preservation, Los Angeles

Statue XVI – Muse, Once Thought to be a Niobe

Nancy and Jeffrey Moreland

Statue XVII – Tormented Psyche

Cynthia and Terry Perucca

Roman Sarcophagus – The Virtues of the Roman Consul

Anne and Rob Krebs and Ann O’Brien

Grisoni’s Rape of Proserpina

Don and Rachel Valentine