Think back to Dante’s lifetime (1265–1321) and count the number of foodstuffs that were unknown to him or his Italy: potatoes, tomatoes, chocolate and maize, to name but a few. Yet somehow the Sommo Poeta was never short of alimentary metaphors when writing about an afterworld where no one needs to eat, but where plenty regret overeating in life. His 14,233-line epic, the Divina Commedia, is after all the most famous work of Italian literature, and it would be strange indeed if the most famous work of Italian literature contained no mention of food.

Gluttony, as codified by St. Thomas Aquinas and others, is one of the seven cardinal sins, and was particularly suspect on account of being but a short step from lust. The first act of gluttony—redundant eating—was Adam’s bite from the apple, which prompted his general fleshy surrender. The two sins are certainly natural bedfellows in one of Dante’s most famous pieces of juvenilia, written long before the Commedia, a tenzone with his friend Forese Donati. A tenzone was a type of poetic mudslinging contest in which the participants strove for the sharpest technique and cattiest insults, and Dante squeezed both illegitimacy and overconsumption into the first four lines of one sonnet:

Bicci novel, figliuol di non so cui

(s’i’ non ne domandasse monna Tessa)

giù per la gola tanta roba hai messa

ch’a forza ti convien torre l’altrui

Young Bicci, son of whom I’m not quite sure

(I’d have to ask Tess if she’s your mother),

the amount you’ve shovelled down has left you poor

so now you need to go and scrounge off others.

“Bicci” gave as good as he got, and the six-poem sequence has survived: gleefully funny, none of it very edifying. In later life, certainly, Dante thought it unworthy of him, and in the Commedia he took pains to engineer a meeting with Forese on the slopes of Purgatory. But though their reunion is emotional and free of snarky references to Monna Tessa, Dante does not retract his other accusation; indeed, Forese is among the gluttons, emaciated beyond recognition, aching for the fruity smells that are wafting off the branches overhead. He and Dante walk and talk until they are startled by the voice of an angel:

Beati cui alluma

tanto di grazia, che l’amor del gusto

nel petto lor troppo disir non fuma,

Esuriendo sempre quanto è giusto.

(Purgatorio XXIV, 151–54)

Blessed are those

who are so lit up with grace that the love

of taste does not smoulder to excess in their breasts,

but always keeps them hungering just enough.

These lines point to the difference between the gluttons in Purgatory—ultimately saved—and their lost counterparts in Hell. Forese and his fellows were guilty of troppo (too much) amor del gusto, but there are worse things to be guilty of. The word amor is the key to everything: amor is never wrong, only sometimes excessive or misdirected. The gluttons in the Inferno, on the other hand, lashed by a filthy black rain that seems to have nothing to do with their sin at all, ate not for love of food but for the aim of feeling physically sated; not for gusto but for a narcotic fug of satisfaction. As such, their punishment is not a deprivation of taste, merely of comfort.

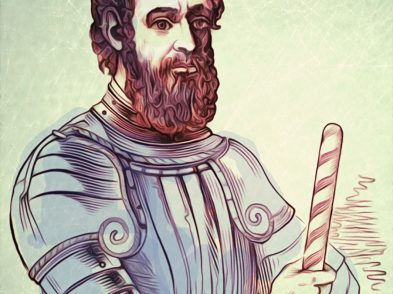

Dante and Virgil, Cerberus and the Gluttons, by Priamo della Quercia (1400-1467)

Exiled in 1302, Florence’s most famous son was estranged for the last 20 years of his life. It was a keen blow: just as an uprooted tree is deprived of its main source of nourishment, so the uprooted Dante felt himself spiritually starved in some way. The Commedia is set in Easter 1300, so Dante’s autobiographical character knows nothing of what awaits him, but the poet broadcast his hindsight through the spirits in the afterlife, who to a greater or lesser extent can see into the future. In heaven he meets his great-great-grandfather Cacciaguida, who warns him, “Tu proverai sì come sa di sale / lo pane altrui”: foreign bread will taste of salt to you. The sense is figurative—the Irish poet W. B. Yeats translated it as “bitter bread”—but also literal: exiled to Verona, Padua and finally Ravenna, the supping Dante could not have failed to taste the difference between local fare and the famously saltless Florentine bread that he had left behind.

And if there is one foodstuff that Dante always returns to, bread it would be. The souls of the proud open Purgatorio XI with a pater noster, metrified into Italian verse. “Da’ oggi a noi la cotidiana manna”, they sing: give us this day our daily bread. Dante frequently wrote of the pane degli angeli (bread of the angels) to mean truth and knowledge, but the more people can eat that bread, the better. He thought of his epic poem, which is meant to be nothing if not instructive, as a kind of “daily bread”, free to anyone who could read or hear it. He started writing the Commedia in Latin, but then realised it would be like giving “solid provender to the gums of suckling babes”. The Italian language, like Italian food, is for everyone, however much easier the food might be to get the mouth around.